Secure Liberty and Justice for All

Why is it important that liberty and justice be for all instead of only for some?

The Pledge of Allegiance states: "I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all."

Why is it important that liberty and justice be for all instead of only for some?

First, because we are all God’s children. We all deserve equal rights and opportunity to make what we will of our own lives.

Second, equal liberty and justice are necessary if America is to live up to its stated ideals and not be hypocritical. President Reagan noted in his July 4, 1986 speech that the U.S. founders “created a nation built on a universal claim to human dignity, on the proposition that every man, woman, and child had a right to a future of freedom.”

At first blush, his statement might seem to be historically inaccurate in the sense that when the founders created the nation, they did not by law or practice honor universal rights to human dignity and freedom for every man, woman, and child. In general, in nearly all the U.S. at its founding, and to varying degrees through U.S. history depending on the time and place, slaves and their children had no rights, racial and ethnic minorities faced discriminatory laws and application of the laws, and women had lesser rights. Thankfully, the U.S. eventually legalized the universality of these rights for all Americans (e.g., in the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and various federal and state laws). But that came to pass only due to long, and sometimes bloody, struggles. So, does that mean President Reagan was wrong to refer to our nation being built on a universal claim to human dignity and freedom? No.

Although the U.S. at its founding did not honor and protect such equal rights, the universality of such rights was inherent in the Declaration of Independence and the political philosophy of many of the American founders. The Declaration of Independence states:

. . . We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, . . . (emphasis added)

This assertion of rights in the Declaration was based on the concept of “natural rights” that come from God (who created all humans, not just people of any particular gender, race, region, or religion) and that cannot legitimately be given up or taken away. In practice, the U.S. (before, at, and for sometime after its founding) denied such equal rights to slaves, women, and various minorities. However, this denial was incompatible with the natural rights ideals of the Declaration and therefore was hypocritical and unsustainable.

This hypocrisy was recognized from the start. Although, unfortunately, some Americans ignored that hypocrisy and continued to deny equal rights, a growing number of Americans took the ideal of universal equal rights for all seriously and worked towards implementing it. From 1781-1783, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court applied the principle of judicial review to abolish slavery, stating the laws and customs that sanctioned slavery were incompatible with the new state constitution. The Chief Justice of the Court wrote: "[S]lavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it can be by the granting of rights and privileges [in the constitution] wholly incompatible and repugnant to its existence." Massachusetts Constitution and the Abolition of Slavery | Mass.gov In 1784, Thomas Jefferson and the other members of the Congressional committee regarding the Northwest Territory proposed to the Confederation Congress (under the Articles of Confederation) that slavery be banned in the territory after 1800. Envisaging the West: Thomas Jefferson and the Roots of Lewis and Clark By one vote, the Congress in 1784 refused to include the abolition of slavery, a fact Thomas Jefferson lamented, saying “The voice of a single individual would have prevented this abominable crime; heaven will not always be silent; the friends to the rights of human nature will in the end prevail.” The Northwest Ordinance and American Ideals – Constituting America But soon thereafter, in 1787, the Confederation Congress adopted the Northwest Ordinance, which permanently outlawed slavery in the Northwest Territory and the states that would be formed from that territory (Michigan, Wisconsin, northeast Minnesota, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois). Northwest Ordinance (1787) | National Archives In order to get southern states to approve the U.S. Constitution in 1787, the northern states agreed (in Article I, Section 9) not to ban the international slave trade before 1808. The majority of Congress was so eager to ban the international slave trade that they passed a law banning the transport of slaves to the U.S., effective on January 1, 1808 (the first date that the ban was Constitutionally permissible). The Slave Trade | National Archives By 1817, every state in the northern and western United States had committed itself to the complete abolition of slavery. In 1828, New York abolished slavery outright, as did Pennsylvania in 1847 (an act that liberated the state’s fewer than 100 remaining slaves). Before There Were “Red” and “Blue” States, There Were “Free” States and “Slave” States – Marquette University Law School Faculty Blog

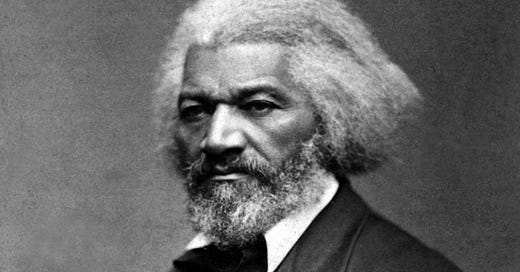

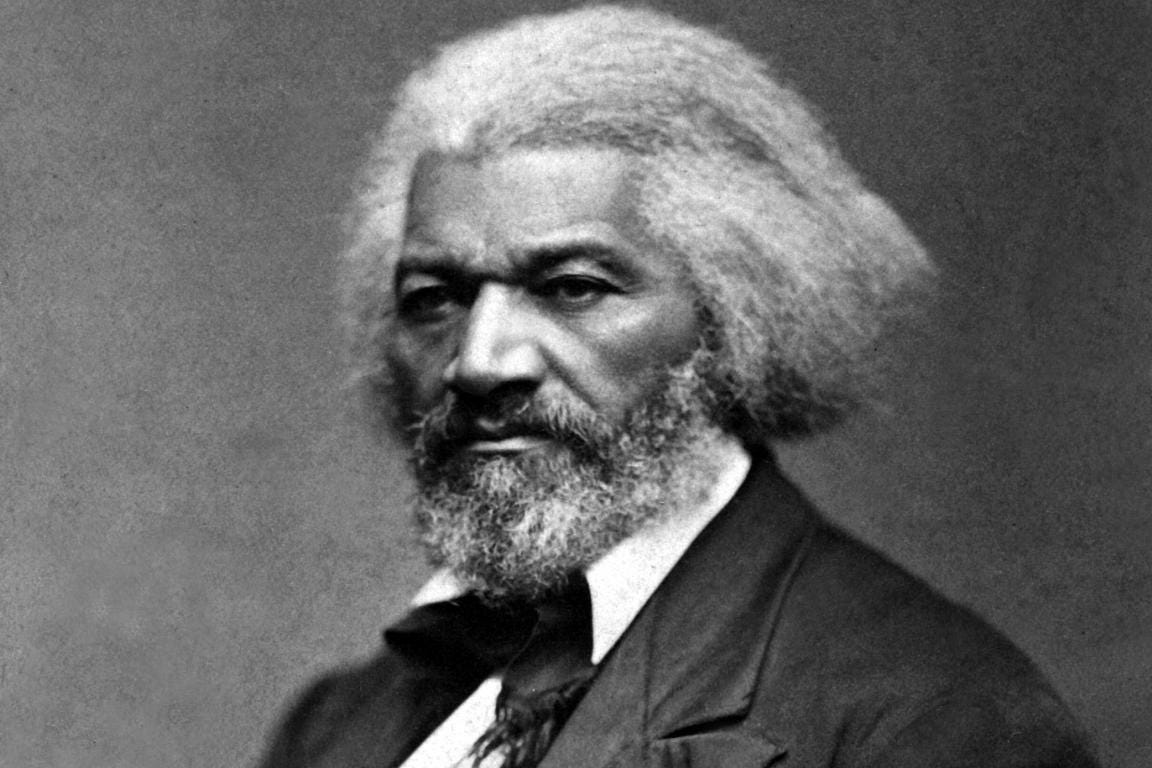

Both the promise of the ideals of natural rights in our country’s founding, and the hypocrisy of denying such rights to some, was eloquently addressed on July 5, 1852 by Frederick Douglass in his speech (popularly known as “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”) to the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Sewing Society.

Frederick Douglass (National Archives and Records Administration)

In that speech, Douglass praised the U.S. founders for their principles, which were a source of hope for achieving universal freedom and rights:

In that instrument [the U.S. Constitution] I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing [slavery]; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a glorious liberty document. . . .

I have said that the Declaration of Independence is the RINGBOLT to the chain of your nation's destiny; so, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in. all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost. . . .

The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men too-. . . I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.

His criticism was not with the country’s founding ideals or its founders, but with the fact that “the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence” were hypocritically selectively denied to some:

This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today? . . .

Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the Constitution and the Bible, which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery—the great sin and shame of America! . . .

There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven, that does not know that slavery is wrong for him. . . .

[Th]e hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced. What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham . . . .

The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretense, and your Christianity as a lie.

Yet he ended his speech with hope that the principles of natural, God-given rights would prevail and end slavery in the U.S.:

Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation, which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. “The arm of the Lord is not shortened,” and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope. While drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age.

The complete text of the speech is available here. A summary of the speech and its context, as well as a video of the speech read by some of Frederick Douglas’s descendants, is available at A Nation's Story: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” | National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Frederick Douglass was right to have hope in our founding principles. Thirteen years after his 1852 speech, slavery was abolished throughout the U.S. as a result of the Civil War that killed more than 600,000 Americans. It is disgraceful that it took another 100 years to end segregation in the South. But that too was inevitable when Americans stood up for the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution (including the 13th, 145th and 15th Amendments). It took some time -- too long – but was bound to happen, since, as expressed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. | Page 5 | Smithsonian Institution (Video)

So, in a longer-run historical context, President Reagan was right to say our nation was built on a universal claim to human dignity and freedom. Even though that dignity and freedom was not available to everyone at the start, a growing number of Americans built a nation that achieved that goal, inspired by the principles in our founding documents.

The history of those struggles is important. It should be taught, and it should be celebrated. But not as a way to try to divide Americans, denigrate our past, or undermine our national principles, as seems to be the goal of those teaching from a Marxist-based “critical” perspective. Instead, it should be done with (1) gratitude for, and a realistic perspective on, the principles and people of the U.S., who have done so much to overcome injustice to bring our country in line with its ideals and bring us together as one people, (2) an honest assessment of the extent to which those ideals have yet to be achieved, and (3) encouragement that all Americans respect and support our mutual right to liberty and justice for all.

That is the vision that President Reagan called for in his Fourth of July speech in 1986. Certainly, he was aware of our country’s divisive history. But he was trying to bring the country together with a message of national unity and brotherhood that transcends our disagreements. So, rather than focus primarily on the injustices and struggles of the past, he celebrated the fact that our country had eventually implemented these universal rights. And he called on all Americans to put aside their differences and to “pledge ourselves to each other and to the cause of human freedom, the cause that has given light to this land and hope to the world.”

Lately, Americans seem to be as divided as ever; split into opposing camps of distrust, and often hatred. But much of that is driven by narratives that too often over-exaggerate or misrepresent our motives and differences. We, and our country, will be much better off if we follow President Reagan’s advice to keep in mind that the things that unite us – the parts of America's past of which we're so proud, and our hopes and aspirations for the future of the world and this much-loved country -- far outweigh what divides us. We should reaffirm that all Americans are one nation indivisible and pledge ourselves to each other and the American ideal of liberty and justice for all.